Leer en español aquí

Regenerative agriculture is a global farming revolution with rapid uptake and interest around the world. Five years ago hardly anyone had heard about it. It is in the news nearly everyday now. This agricultural revolution has been led by innovative farmers rather than scientists, researchers and governments. It is being applied to all agricultural sectors including cropping, grazing and perennial horticulture.

In previous articles we have described how regenerative agriculture maximizes the photosynthesis of plants to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to increase soil organic matter. Soil organic matter is a good proxy for soil health, as it is important for improving fertility and water capture in soils, thus improving productivity and profitability in farming.

Many regenerative farmers sow their fields with mixtures of plants just to capture carbon dioxide to improve the levels of soil organic matter. These are called cover crops and are distinct from the cash crop. The cover crop builds soil fertility. The cash crop earns an income.

Pasture Cropping—the No-kill, No-till System

Australia has many innovative regenerative farmers. The two farmers below are pioneers of a cover cropping system called pasture cropping. This is where the cash crop is planted into a perennial pasture instead of into bare soil. There is no need to plough out the pasture species as weeds or kill them with herbicides before planting the cash crop. The perennial pasture becomes the cover crop.

This was first developed by Colin Seis in New South Wales. The principle is based on the sound ecological fact that annual plants grow in perennial systems. The key is to adapt this principle to the appropriate management system for the specific cash crops and climate.

The pasture is first grazed or slashed to ensure that it is very short. This adds organic matter in the form of manure, cut grass, and shed roots into the soil to build soil fertility and to reduce root competition from the pasture. The cash crop such as oats is directly planted into the pasture.

Image courtesy of Colin Seis

Here’s Colin Seis’s own description of pasture cropping:

“A 20-hectare (50 acre) crop of echidna oats that was sown and harvested in 2003 . . . This crop’s yield was 4.3 tonnes/hectare (31 bushels/acre). This yield is at least equal to the district average, where full ground-disturbance cropping methods were used.”

“This profit does not include the value of the extra grazing. On Winona, Colin Seis’s farm, it is between $50–60/hectare because the pasture is grazed up to the point of sowing. When using traditional cropping practices where ground preparation and weed control methods are utilized for periods of up to four to six months before the crop is sown, no quality grazing can be achieved.”

“It was also learnt that sowing a crop in this manner stimulated perennial grass seedlings to grow in numbers and diversity, giving considerably more tonnes/hectare of plant growth. This produces more stock feed after the crop is harvested and totally eliminates the need to re-sow pastures into the cropped areas. Cropping methods used in the past require that all vegetation is killed prior to sowing the crop and while the crop is growing.”

Image courtesy of Colin Seis

“From a farm economic point of view, the potential for good profit is excellent because the cost of growing crops in this manner is a fraction of conventional cropping. The added benefit in a mixed farm situation is that up to six months extra grazing is achieved with this method compared with the loss of grazing due to ground preparation and weed control required in traditional cropping methods. As a general rule, an underlying principle of the success of this method is 100 percent ground cover 100 percent of the time.”

Other benefits are more difficult to quantify. These are the vast improvement in perennial plant numbers and diversity of the pasture following the crop. This means that there is no need to re-sow pastures, which can cost in excess of $150 per hectare, and considerably more should contractors be used for pasture establishment.

Independent studies at Winona on pasture cropping by the Department of Land and Water have found that pasture cropping is 27 percent more profitable than conventional agriculture; this is coupled with great environment benefits that will improve the soil and regenerate our landscapes.

Pasture cropping is one of the best ways to increase soil organic matter. The fields are covered with photosynthesizing leaves all year, capturing CO2, which are deposited deep into the soil by the roots of perennial cover crops. Dr. Christine Jones has conducted research at Colin Sies’s property showing that 168.5 tons of CO2 per hectare (170,000 pounds/acre) were sequestered over the course of ten years. The sequestration rate in 2009–2010 was 33 tonnes of CO2 per hectare per year.

This huge addition of soil organic matter has stimulated the soil microbiome to release the minerals locked up in the parent material of the soil, dramatically increasing soil fertility. The following increases in soil mineral fertility have occurred in ten years with only the addition of a small amount of phosphorus:

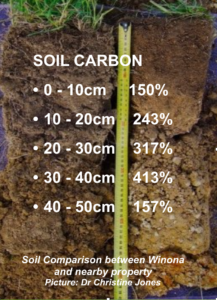

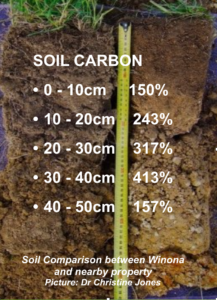

A soil comparison between Colin Seis’s farm (Winona) and a nearby property shows significantly improved soil carbon levels in areas that have been pasture cropped. 10cm = 4 inches. Image courtesy of Dr. Christine Jones.

Calcium 277%

Magnesium 138%

Potassium 146%

Sulphur 157%

Phosphorus 151%

Zinc 186%

Iron 122%

Copper 202%

Boron 156%

Molybdenum 151%

Cobalt 179%

Selenium 117%

The Soil Kee System

An excellent example of the development of pasture cropping / no-till no-kill is the Soil Kee, which was designed by Neils Olsen.

First the ground cover/pasture is grazed or mulched to reduce root and light competition. Then the Soil Kee breaks up root mass, lifts and aerates the soil, top-dresses the ground cover/pasture in narrow strips, and plants seeds, all with minimal soil disturbance. The seeds of the cover/cash crops are planted and simultaneously fed an organic nutrient such as guano. The faster the seed germinates and grows, the greater the yield. It is critical to get the biology and nutrition to the seed at germination and to remove root competition.

A perennial pasture a few days after the Soil Kee was used to break up the root mass and plant the seeds of the cover crop.

Pasture cropping is excellent at increasing soil organic matter/soil carbon. Neils Olsen has been paid for sequestering 11 tonnes of CO2 per hectare (11,000 pounds/acre) per year, under the Australian government’s Carbon Farming Scheme in 2019. In 2020, he was paid for 13 tonnes of CO2 per hectare (13,000 per acre) per year. He is the first farmer in the world to be paid for sequestering soil carbon under a government regulated system.

Niels Olsen with a multispecies cover crop of legumes, grasses, and grains for livestock. This mix grows strongly in mid-winter. Cereals, pulses, and other cash crops can be planted into the pasture to produce high-value cash crops.

Regenerative agricultural systems such as cover cropping and pasture cropping are radically changing the conventional approach to weed management. They have shown that the belief that any plant that is not our cash crop is a weed and needs to be destroyed is no longer correct. The fact is that plant diversity builds resilience and increases yields, not the other way around. The key is developing management systems that change competition from other plants into mutualism and symbiosis that benefit the cash crop.

Multispecies cover crops produce more biomass and nutrients than single-species monocultures. In the example of the Soil Kee system, the amount of stock feed is more than double the usual perennial or annual pastures in the district.

Variations of these systems are being developed all the time and are being used very successfully in horticulture, grazing and broadacre agriculture. To quote Colin Seis, “as a general rule, an underlying principle of the success of this method is 100 percent ground cover 100 percent of the time.”

Andre Leu is the International Director for Regeneration International. To sign up for RI’s email newsletter, click here.