In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations in the U.S. and Latin America that save, produce and sell seeds have seen a significant increase in the demand for native seeds. This new interest in seeds comes with great opportunities, but also some challenges.

Motivated to learn more about this phenomenon, Valeria García López, a researcher in agroecology in Colombia and Mexico, and David Greenwood-Sánchez, a political scientist specializing in GMO regulation in Latin America, set out to do some research.

Both López and Greenwood-Sánchez are independent researchers who in recent years have been part of different movements in defense of seeds in Latin America and the U.S. Both believe that this new interest in seeds, in the context of the current economic, food and health crisis, highlights the challenges local seed systems are facing in a post-pandemic scenario.

We recently spoke with López and Greenwood-Sánchez to learn more about their work, their love for seeds and biocultural diversity, as well as the motivations for their research.

Seeds and biocultural diversity: a love story

Greenwood-Sánchez is a native of Minnesota but his mother is Peruvian. He has a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics and a Master’s Degree in Public Policy. During his studies, he had to do an internship and decided to do it in Peru, looking for his roots.

Over the course of his research, Greenwood-Sánchez found out that Cusco, a city in the Peruvian Andes, had declared itself a GMO-free region, thanks to a push by potato growers and the existing moratorium on GMOs in Peru. Curious to know more, Greenwood-Sánchez ended up doing an internship at the Parque de la Papa (Potatoe’s Park), an association of five indigenous communities that manages more than 1000 varieties of potatoes and works on issues related to biodiversity, intellectual property and biocultural records. There, he discovered agrobiodiversity and its link to culture and traditions, and how people can promote agrobiodiversity through their culture and day-to-day life. He then decided to pursue a Doctorate in Public Policy at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

David Greenwood-Sánchez planting potatoes in Minnesota

Greenwood-Sánchez’s research has focused on the construction of systems that regulate GMOs in Latin America, using Mexico and Peru as case studies. In Mexico, certain GM crops can be planted, while in Peru, there is a moratorium on GMOs. His research focuses on the different groups that come together for the defense of biodiversity, on how the state, society and global markets join their efforts to demand policies that regulate the use of GMOs. This is closely related to the identity of each country, its people and how that identity is connected to their biodiversity, for example corn in Mexico, or potatoes in Peru.

García López is Colombian, but has been living in Mexico for five years. For the past six years she’s worked with networks of seed keepers, mainly in Antioquia, where she is originally from. She studied biology and then did her internship on agrobiodiversity and orchards in southern Colombia, near the border with Ecuador. There she discovered the wonders of agrobiodiversity. Being in love with the High Andean region, she went to Ecuador, where she did a Master’s Degree in conservation of the páramo ecosystem and its relationship with climate change.

Back in Colombia, García López discovered the Colombian Free Seeds Network (RSLC). But in Antioquia, her native region, there was no local seed network, so she and other people were assigned to work to create a division of the network RSLC. Since the end of 2014, she worked to support the creation of community seed houses that would represent the first steps to create a Participatory Seed Guarantee System (GSP). That system would allow a certification of agroecological seeds under criteria internally established by the territories themselves, by indigenous and small farmers’ organizations—not by external entities, whether private or public.

This process has also allowed for progress toward the declaration of GMO-free territories. By taking advantage of protected indigenous reserves, which are exempt from complying with the Free Treaties Trade, García López and others were able to ban GMOs from the indigenouse reserves, and create a program to promote the conservation of native seeds.

García López recently completed her PhD in Ecology and Rural Development at the Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), Mexico. The topic of her research was how seed guardian networks use different strategies to defend seeds. She studied cases both in Mexico and Colombia after observing that in both countries, the defense of native and creole seeds has intensified and how seed networks have come together to face threats. In fact, seed initiatives that had already existed but worked in isolation are now joining forces around a common goal.

Valeria García López holding a huge and beautiful squash she just harvested.

COVID-19 as catalyst for the agroecological movement

The pandemic of 2020 has exposed the fragility of the conventional food system, with its agribusiness corporations and long supply chains. Food supply problems, especially in urban centers, as well as an increase in prices and speculation have only been symptoms of this fragility.

Today, it is the small farmers who in many places keep local supplies going. In Brazil, for example, farmers from the Landless Workers Movement (MST for its Portuguese acronym) are donating food to people living in the cities. Organized movements in the countryside are mobilizing a lot of food, showing the capacity of alternative movements to respond.

The relationship between food and health is another topic spotlighted by the pandemic. People with chronic diseases linked to bad eating habits—diseases such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension and high cholesterol caused by bad eating habits—are more vulnerable to the virus. In fact, the strength or weakness of the immune system is greatly determined by our diet.

Hippocrates, father of modern medicine, said it more than 2,500 years ago: “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” This is why many people today are paying more attention to the food on their plates, its origin, how it was cultivated. People are more interested than ever in healthy eating, planting and having home gardens, and buying local food directly from the producers.

The pandemic has been shown the need to promote local agro-ecological food systems, which have proven to be more resilient than agribusiness systems. In this context, local and resilient seed systems become especially relevant, as they are the foundation upon which food sovereignty is built.

Pandemic times: Panic or hope? Looking for the seeds of change

García López and Greenwood-Sánchez are motivated to show there is hope despite the current global health and economic crisis. They decided to look beyond the mass media’s panic-inducing narrative about food insecurity, and investigate for themselves what was happening with producers. In particular, they wanted to know more about the initiatives related to the defense, reproduction, exchange and commercialization of native seeds, with the aim of learning and preserving traditional knowledge and practices in times where resilient and regenerative systems are much needed.

To carry on their research, they followed up on the news, and they conducted a series of surveys and personal interviews (though not face-to-face, to comply with current social distancing). More than 25 initiatives from six countries in the Americas participated in the research: U.S., Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Argentina and Peru. Medium-sized and family owned companies and individual, community, rural and urban initiatives gave their insights.

Here are some of the conclusions they drew from their research:

- People are going back to appreciating what’s essential, the common goods, what sustains life. The crisis highlights the need to know where our food comes from, the importance of soil, water, and food justice.

- More people are realizing the importance of growing their own food. Many people and organizations are now more aware of the importance of growing food for self-consumption. Many are starting their own gardens for the first time.

- There’s a greater appreciation for the work seedkeepers do. The pandemic has generated greater awareness regarding the importance of food and farmers, as well as the role of seedkeepers who have preserved agrobiodiversity in a traditional way and who also have the knowledge on how to cultivate and care for seeds.

- There’s renewed interest in seeds and food exchanges. Many traditional practices from indigenous people, such as Ayni in the Andean region, are becoming even more valuable today and inspire new forms of collaboration through networks of trust, support and solidarity.

- People are realizing the need to be more creative to meet the rising demand for seeds. Many seed initiatives and ventures have been overwhelmed by the growing demand, exceeding their capacity to respond, and have had to creatively restructure their work in order to cope with the explosion of orders.

Collective planting. Photograph by Valeria García López.

Who is behind the growing demand for seeds?

García López and Greenwood-Sánchez have found that it is not so much the institutions, companies or the government but the people and the communities who have been organizing themselves to acquire seeds and plant them. People are very interested in finding solutions and helping other people, out of pure solidarity.

Greenwood-Sánchez mentions, for example, an initiative that he promoted together with a group of friends, which today brings together about 700 people. The “Twin Cities Front Yard Organic Gardeners Club” encourages people to grow food on their front yard. Traditionally, in U.S. cities, people would have their vegetable gardens in the backyard, a custom that was especially adopted after the Second World War (Victory Gardens). In general, in the front yard there is just grass. But this is changing with the growing movement to replace grass with food.

Front yard being turned into a vegetable garden. Photo by David Greenwood-Sánchez

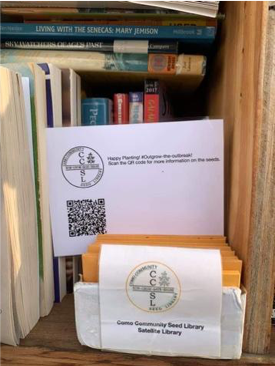

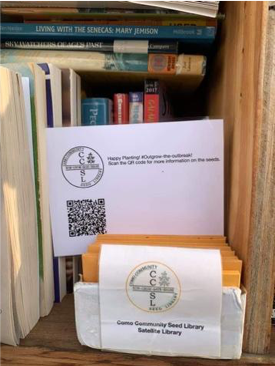

Another example in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where Greenwood-Sánchez lives, is the “Outplant the Outbreak” campaign, which consists of making seed packets and putting them inside boxes where books are normally put, for public use and for free.

Envelopes with seeds for free. Photo by David Greenwood-Sánchez

In Peru, the government has started a campaign called “Hay que papear” to address the crisis by promoting potato consumption, as a complete, nutritious and cheap local food, and also to counter the general tendency to devalue this crop and to make its producers more invisible.

With growing interest come new challenges

While interest in seeds and growing food has spiked during the pandemic, the uptick in interest has revealed new challenges. As part of their research, García López and Greenwood-Sánchez identified some of these challenges and potential solutions, including:

- The greater demand for open-pollinated seeds requires a necessary increase in supply, which poses challenges in the organizational, technical, training, economic and legislative areas. Structural changes are needed to facilitate the growth and development of this sector.

- Current seed laws and international treaties favor transnational seed companies and the promotion of GMOs. These laws threaten local seed systems, which are the basis of food sovereignty. Some examples are UPOV 91, the Seed Production, Certification and Commercialization Law or the Reforms to the Federal Law of Plant Varieties, in Mexico. To strengthen people’s food sovereignty, the first step should be to curb these treaties and laws and promote those that strengthen local seed systems, which have proven to be much more resilient against supply chain outages and the climate crisis. Fortunately, the greater awareness of the importance of agriculture and food, as well as the greater interest in growing your own food, is also bringing to the table the importance of these seed laws and treaties.

- There need to be efforts to create public policies and laws that stimulate and strengthen local seed systems, including structural reforms at the market level to allow commercialization and seed exchange initiatives that cannot be subject to the same certification criteria as large transnational corporations.

- One of the main arguments against the creation of seed laws that regulate and control the production of native and creole seeds is that the production of these seeds is not stable, unique or homogeneous. The main value of native and creole open-pollinated seeds is their genetic diversity, which gives them enormous capacity to respond and adapt to new geographic and climatic conditions. In Colombia, over a period of three years, several workshops and forums were held at the local and national level in order to identify the most important principles for seed guardians. The Participatory Guarantee Systems (SPG) has put together its own criteria, based on seven principles. It should be noted that one of the criteria of the Network of Free Seeds of Colombia regarding the sale of seeds specifies that in fact seeds themselves are not sold. What is sold is all the work behind the seeds, and what makes their existence possible. This is great progress, since it recognizes seeds as a common good which cannot be commercialized.

- It is necessary to promote and protect the autonomy of the communities that have been practicing agriculture and that have cared for, selected and multiplied seeds for thousands of years. They do not need external validation, because these are practices that they have done for a long time. The challenge, rather than imposing external rules, is to ask ourselves how we can support them, how we can be useful for their work to prosper.

- As more and more people start to grow their own food for the first time, it is essential to generate and promote educational spaces or gardens where these people can learn how to plant and maintain their gardens. It is important to understand the seeds should be planted, not saved and accumulated. Using them, multiplying them, exchanging them, donating them is the way to go.

Next steps

Once García López and Greenwood-Sánchez complete the analysis of their research, they will share the results with all those who participated. They will also create a report, using plain language so it is suitable for the general public, to highlight the challenges that local seed systems face with this growing interest for native and native seeds.

Would you like to know more about the work Valeria and David do?

Write them a message: vagarcialopez@gmail.com, davidgreenwoodsanchez@gmail.com

Claudia Flisfisch Cortés is an agroecology specialist who is part of the commission of seeds and the articulating commission of RIHE (Chilean Network of Educational Gardens).To keep up with Regeneration International news, sign up for our newsletter.